An Apologia for the Church of England

Anglicanism as the English expression of the Catholic faith

This week’s article was going to be on the Catholicity of the universal Church. I have been working on a piece about the whole Church in my continued hope for Christian unity. But something more pressing has come to my attention this week.

The Church of England shared a link on social media to its webpage, History of the Church of England. This post caused major backlash, which resulted in the CofE disabling replies on Twitter.

The tweet in question read, “The Church of England is the established Christian church in England.

Our roots go back to the time of the Roman Empire, when the church came into existence in what was then the province of Britain.

Find out more about our history at http://cofe.io/OurHistory.”

Fairly benign, one might have thought, until one reads the replies, particularly from Roman Catholics. The seething genuinely caught me off guard. Now, anyone who follows my work will be aware that I am no fan of the Church of England as an institution. I left a couple of years ago in a rather public spat, so there is no love lost between us. However, they are right in this. The Church of England’s history is far more interesting and nuanced than this revisionist take that “the fat philanderer Henry VIII invented a new Church and the Church of England has no Catholic roots.”

Regular readers will know my theology is incredibly Catholic. Most protestants think I am a swift breeze away from swimming the Tiber. I have my issues with the contemporary interpretation of papal supremacy. This week, I learned there is another dogma I do not share with my Roman brethren, and that is the outright denial of the Church of England’s Catholic roots.

Henry VIII is responsible for some awful atrocities. Eamon Duffy covers them well in his Stripping of the Altars. The dissolving of the monasteries is one of the greatest crimes in English history — absolutely awful. And I have written previously on how the Reformation was a mistake. Any Church split is bad for Christian unity; the Body of Christ is supposed to be whole.

That said, Henry VIII was a human being like the rest of us, a fallen individual. History is not black/white, and we can paint him as a villain all day long. But it is important to look at history holistically and address the whole picture. His rottenness does not take away the Church’s heritage. Even he did not have that power.

In retrospect, had Pope Clement VII annulled Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon and given him the opportunity of being blessed with a son to produce an heir to the throne, much of the mess of English Church history could have been avoided. The Pope would not have been setting a precedent. This was perhaps a political decision, not a theological one. The Holy Roman Emperor Charles V was Queen Catherine’s nephew, and he had taken control of Rome. The Pope refused to disolve Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine for that reason, it had little to do with the sanctity of marriage, unfortunately. But that point is neither here nor there.

Henry VIII was a Catholic king. The reason the present King of England is called Defender of the Faith (Fidei Defensor) is because Parliament bestowed the title on Henry VIII and his successors to defend the Anglican faith. Prior to that, though, Pope Leo X bestowed it upon Henry VIII for his book Defence of the Seven Sacraments (Assertio Septem Sacramentorum). In Defence of the Seven Sacraments, Henry VIII outlined the importance of the Sacraments in what was called “one of the most successful pieces of Catholic polemics produced by the first generation of anti-Protestant writers.” Henry VIII called Martin Luther a heretic - which is quite ironic considering how many Anglicans venerate Luther today.

Being incredibly Catholic, Henry VIII did not set out to create a Protestant Church, certainly not in the same guise as Protestantism on the continental of Europe.

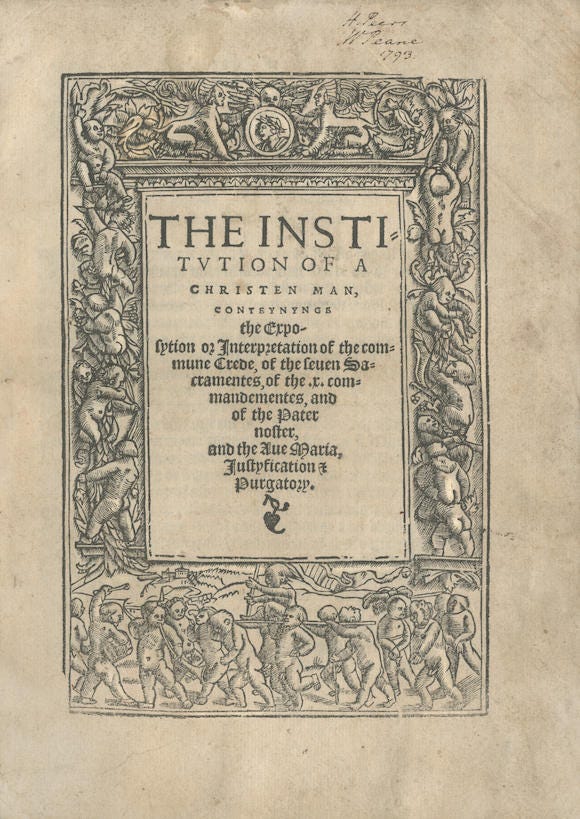

Henry VIII got divorced and secretly married anyway; he was excommunicated, and in return, he split the English Church from Roman authority. In 1536, Henry VIII gave sanction to his Ten Articles of Religion, which became the foundation of the Bishop’s Book (otherwise called The Institution of the Christian Man). Over the next three years, this work progressed to become the King’s Book, containing Six Articles of Religion for the Church of England, “The articles reaffirmed Catholic doctrine on matters of transubstantiation, the reasonableness of withholding the cup from the laity during communion, clerical celibacy, observance of vows of chastity, permission for private masses and the importance of auricular confession.” [1539] This was not your grandma’s Protestantism.

Henry VIII was hardly a Continental Protestant, but he did become a reformer. We take it for granted now that everyone can access the Bible in their native tongue - but it is Henry VIII who first commissioned an English Bible. Pope Paul II prohibited Bibles in vernacular languages, and violators were punished. The Rheims-Douai Bible was later allowed (1582-1610) but for the purposes of Roman Catholic exiles from England in France to avoid any errors/bias from the Protestant translations. Access to the English Bible is a direct result of the Reformation. The Coverdale Bible was to be placed in every church in England.

King Henry VIII instituted the first English liturgy, too, with the Great Litany. He commissioned direct translations from Latin to English, thus avoiding the problems the Novus Ordo faced with removing important parts of the liturgy. It could be argued that Henry VIII was less of a liturgical reformer than the Second Vatican Council.

Anglican Kings and Queens

King Henry VIII’s son, Edward VI, was a young king at nine years old, and it seems he was surrounded by Protestant advisors. He led the English down a more Protestant path, but his tenure was short-lived. He only sat on the throne for six years. Unfortunately, he caused some lasting damage during that time, which we will get to.

Henry VIII’s daughter, Queen Mary I, became Queen and attempted to reunite the Church of England with the Church in Rome. Unfortunately, her methods led her to be known as Bloody Mary. She burned Protestant heretics at the stake. Neither side of the Reformation came out smelling of roses. Anti-Catholic sentiment rose, and under her sister Elizabeth I’s reign, Catholics were persecuted just as badly. I do not intend to paint this as a tit-for-tat; prominent Catholics like St Thomas More had previously been killed under Henry VIII for not submitting to his supremacy. The Reformation and Counter-Reformation is a grave stain on English Christian history.

Queen Elizabeth I attempted a compromise with her 39 Articles. She was excommunicated by Papal Bull. Ever since then, the Church of England has been independent from Roman jurisdiction. It may have been Henry VIII’s actions that led to this moment, but he did not create a new Church. The Church of England split from Rome and was never able to reunite fully. But she was not a new invention.

The British Empire spread Christianity around the world and did so in the English expression, which came to be known as Anglican. The Anglican Communion grew from churches in communion with Canterbury, outside of communion with Rome.

Apostolic succession

In 1896, Pope Leo XII declared in his apostolic letter, Apostolicae curae, Anglican ordinations to be “absolutely null and utterly void.”

But based on what? A misinterpretation of the Form and Manner of Making, Ordaining, and Consecrating of Bishops, Priests, and Deacons in the Book of Common Prayer — a particular liturgy that only existed between 1552 and 1662 — a sixty-year blip, if anything.

The Book of Common Prayer, which contains the approved liturgies of the Church of England, went through a few iterations in the battle between Catholicism and Protestantism. Generally speaking, the original 1549 was still fairly Catholic, the 1552 was more Protestant, and the final version in 1662 was held to be the via media of Anglicanism. The middle way between Protestantism and Catholicism. The 1662 BCP is still the official liturgy of the Anglican Church, all these years later. The beautiful language and liturgy have since been adapted into the Latin Rite via the Ordinariate’s Divine Worship Missal and Divine Worship Daily Office books.

The Ordinal - the order for ordaining deacons, priests and bishops - in the 1552 BCP introduced under King Edward VI was vague on the purposes of ordination, and Pope Leo XIII took it as a “defect of form and intention,” claiming that as a result Anglican orders were “absolutely null and utterly void.”

This is a line I have seen Roman Catholics throw at Anglicans quite often as a dismissive attempt to demean them. Not only does it lack charity, it lacks critical thinking. Just because a pope said it does not make it true. The pope was not speaking infallibly. As I understand it, the pope is only infallible when he speaks ex-cathedra. The Roman Catholic Church declares that the only time the pope has spoken infallibly since the Council of Vatican I is on the statement of the Assumption of Mary as an article of faith. Since Vatican I was in 1870, and Apostolicae curae was issued in 1896, it suffices to say this was not an infallible statement.

Also, if Henry VIII broke from Rome in 1533 and the new Ordinal did not come into play until 1552, would that mean there were two decades of valid but illicit ordinations taking place in the Church of England? It seems that would be the case - and this provides further proof of the continuation of the Church and an affirmation of the Church of England’s Catholicity.

The Archbishops of Canterbury and York's response to Apostolicae curae was Saepius officio, in which the Archbishops demonstrated Biblical validity. More importantly, they pointed out that Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox liturgies would be found guilty by the same measure as those of which they were accused.

During Queen Mary’s reunion of the churches, not a single priest was deprived due to a ‘defect of order.’ Many remained in office without re-ordination. Some were even promoted in the Roman Catholic Church.

Even if it were true that Anglican orders were null and void in 1896, would it still be the case today? Old Catholic and Eastern Orthodox bishops have been involved in Anglican consecrations since the Bonn Agreement in the 20th century. In 1922, the Patriarch of Constantinople recognised Anglican orders as valid.

Other developments in this area have occurred. This year, Pope Francis and the Archbishop of Canterbury commissioned a pair of Anglican and Roman Catholic bishops at a joint ceremony. Pope Paul VI gave his ecclesiastical ring to the Archbishop of Canterbury. Justin Welby has inherited this ecclesiastical ring from his predecessors.

In my humble opinion, Anglican orders have only come into question since 2015, when they consecrated the first woman bishop. Since women cannot become priests or bishops, and the Church of England does not have the authority to unilaterally decide otherwise, anyone ordained since 2015 would need to provide evidence of their apostolic succession to demonstrate that they were not ordained by a woman, or by someone who was ordained by a woman. The waters have been muddied, but this is a very recent innovation.

The conclusion of the Anglican–Roman Catholic International Commission of 1990 stated:

The purpose of the present survey has been to draw attention to the changing climate between the Anglican and the Roman Catholic Communions since the condemnation of Anglican orders by Leo XIII. There has been a growth in understanding and friendship between members of the two Churches. Vatican Council II marked a point of no return. With the creation of the Pontifical Council for Christian Unity, the wish to substitute dialogue for polemic was given an institutional instrument. The movement of rapprochement has begun to bear fruit in the work of ARCIC I, ARCIC II, and a number of regional and national joint Commissions.

Anew context for the resolution of pending problems between the Churches is thus in the making. This context is now posing new questions. Among them there is that of a possible re-evaluation of Anglican orders by the Roman Catholic magisterium. To what extent the new context allows for new approaches to the apostolic letter Apostolicæ Curæ and to its conclusion is a question that deserves discussion. To what extent this context has also been negatively affected by the ordination of women in the Anglican Communion is itself a point that should receive careful examination.

At the conclusion of the present report, ARC-USA invites theologians of their two Churches to assess anew the past and present climate of their relationships, as well as this report, and to suggest possible ways forward to preserve and promote the ecumenical impact of Vatican II and of the recent dialogues, even in the face of whatever serious difficulties still exist.

ARC-USA trusts that its own efforts will contribute to the clarification of at least some of the issues involved in the assessment of the new context in which the Churches now live.

The Catholic Heritage of the CofE

Regardless of whether one thinks Anglican orders are valid or not, whether one thinks the Reformation was a success or not, or whether one likes Henry VIII or not, it is silly to argue that the Church of England is an entirely separate entity from the Church in England before the Reformation and that it is a new invention, completely separate of any heritage.

The Church in England was active prior to St Augustine - the first Archbishop of Canterbury, sent by Pope Gregory I. It is assumed that Christians arrived in England via France because there is evidence of Christian activity as early as the second century. Records of the Council of Arles in 314 AD and the Council of Ariminum in 359 AD show the presence of British bishops. By the time authorities arrived in England from Rome in 597 AD, there were many Christians living across these lands. It is well documented that one of Augustine’s first challenges was to unite them all under his authority. That included Christians from Wales, Cornwall, Iona, and Lindisfarne, to name a few. And the English battle against foreign authority never ceased. The Church of England was not under direct Roman authority until 664 AD, and that is only because the Roman and the Celtic Christians were fighting over the liturgical calendar, and they had to seek a higher authority to settle the matter of which date Easter would land on. The problem of authority, however, was never truly resolved.

There were grievances over Peter’s Pence (foreign taxation) and, of course, the issue of the now infamous indulgences being used to fund St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. There were many issues bubbling up under the surface around the time of the Reformation, which could essentially be seen as the first Brexit. The split from Rome was not theological but ecclesiastical. The Church of England did not cease being Catholic; it ceased being under Roman authority. There are those who would say they are one and the same, and I address that in my next article, which will more broadly explore Catholicism and Catholicity.

It has not always been the case that the Bishop of Rome appoints bishops in foreign lands, for example. Roman Catholic author Eamon Duffy writes on this in Faith of Our Fathers, that investiture has traditionally been a local authority. Princes of the land (i.e. the King or Queen) used to select their own bishops. The Pope only really acquired that power universally relatively recently. The matter was settled after a protracted conflict between the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor in the Concordat of Worms, and the German Emperor retained the right to preside over the election of abbots and bishops. In return, the Holy Roman Emperor renounced his right to select the Pope. This is a battle that had previously played out in England, too, with the then Pope contesting King Henry I of England for that authority, which was resolved in the Concordat of London.

All this to say, the Church in England has always held tensions against Roman authority. We tend to think the Church was Roman until the Reformation, but in fact, the Church in England has only been under direct Roman authority for half of its existence. Although, it is fair to say the Church in England was always in communion with Rome, until after the Reformation.

So, yes, the annulment (or lack thereof) played a large part in the Church of England’s divorce from Rome, but that was not the only contributing factor. The English have always been Christian but not always accepted Roman authority. We have had a rough history, but it most certainly is a history. To suggest that the Church of England began in the 1500s is a revisionist approach at separating her from her Catholic lineage.

Anglicanism has become known as the English expression of the Catholic faith. Roman Catholics will no doubt take issue with that, as will many Protestants. But the Church of England is not a new religion. You can say they entered schism or even that they became apostate - as I have in the past. But to suggest it is an entirely new entity without any Catholic roots or heritage is ludicrous.

One should never underestimate the human capacity to want to make everything binary. We really are losing all capacity to observe nuance. We want to live in a Marvel world of heroes and villains. That is simply not the case here, nor is it realistic. Most of the canonised Saints lived checkered lives and did some pretty awful things. Surely, the Christian message is one that we are all sinners, yet we can always repent of our sins and grow in our faith in Jesus Christ as our Lord and Saviour. He died for us, and he forgives us. He offers us eternal salvation, and that is never unachievable. Even for a man like Henry VIII.

Thank you for a fascinating article, I have learnt a lot and look forward to your article about Catholicism. I am thinking of seeking sanctuary from modern Anglicanism in the RC church.

Spot-on Fr. Calvin! I've been attempting to present the very same facts to a number of Roman Catholics I know, and the replies I get are just short of diabolical. We who have fully vetted the history of the Church IN Brittania, know that they predated the Church OF England, and, in fact, predated the Church of Rome. After all, we do see the bishops of England at the Council of Nicaea long before the Roman Catholic Church took over leadership of the the Church in England.